Microsoft Kin Creators Reflect on What Was Cut and Planned

It’s impossible for a company as prolific as Microsoft to not make at least a few stinkers. But their first attempt to release a mobile phone under their own brand could not be described as anything but a disaster. Kin phones, released at the dawn of the current mobile landscape, were discontinued just six weeks after their US launch. It took a multitude of factors to make it fail — the feature set was not great for a targeted demographic, the competition was strong, and Verizon’s plans were just too steep.

Behind the story of a giant company releasing a dud (don’t we all love them, if only instinctively?) lies another one — of hard work and hopes for the future. For all its cons, Kin’s deep social integration, if implemented better, could make a difference in a bloodbath of 2010 mobile phone market.

Instead of making a summary of what we already know of Kin, I’ve decided to talk to people involved in its creation. Not only they shed more light on why Kin turned out to be the way it was, but also showed Microsoft was interested in evolving their phones over time — if only they didn’t flop.

Three-dimensional UI: too much for first-gen Tegra?

Microsoft had the presence in the mobile market since the 1990s, licensing their Windows CE operating system to device manufacturers. Kin One and Kin Two, on the other hand, were the company’s first attempts at releasing its own complete product. They were not traditional smartphones, though, but feature phones with touch controls and a subset of iPhone and Android functionality.

In 2010, before the influx of cheap Android handsets, it was yet sensible to release so-called “touch phones.” Kin phones and their contracts, however, weren’t cheap, and the platform, being targeted to teens and tweens, notably lacked features vital to the digital generation — Internet chats, for example.

The software issues could realistically be resolved over time, as Microsoft implemented an over-the-air update system. The hardware, though, was here to stay, and the choice of components raised the eyebrows even back then. Kin phones marked the first time Tegra, Nvidia’s system-on-a-chip, was used in a mobile phone. But it was the aging APX 2600 chip, first used in Microsoft’s Zune HD media player, while devices powered by next-generation Tegra were already announced at that point.

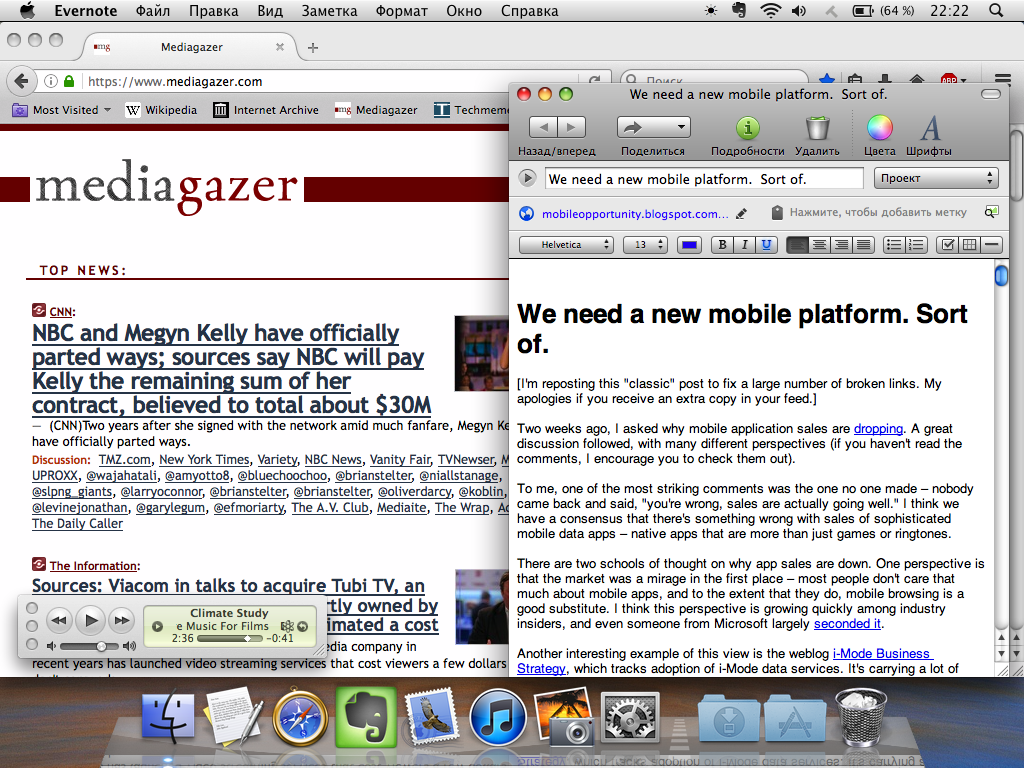

The chip might be one of the causes for performance woes, documented well enough in regards to both final and pre-release hardware. In 2012, Wired obtained internal videos showing how poorly the system responded to swipes and touches, among other things.

The videos have vanished from the source by now. One of them was uploaded to YouTube; I’ve mirrored it to the Internet Archive.

It’s hard to imagine the UI was initially going to be way more visually impressive. Erik Hunter, who was working for a design studio Method at the time, was responsible for the UI motion design of Kin phones. According to him, Method and Kin’s lead designers collaborated on creating a three-dimensional, motion-rich UI. The look, featuring a drastically different design language, is shown on Hunter’s web site.

“There were lots of interactions which didn’t end being developed, like the motion on the lock screen, the Spot [sharing widget] icon animation, and the scrolling tiles. Most of the interactions and animations we designed ended up not being possible,” says Hunter, citing the processing power and the features being cut in development.

One of the visual features implemented at some point was the 3D effect on the Loop, a home screen displaying social media updates. Chris Furniss, responsible for implementing the UI on device with XAML and Silverlight, was involved in downscaling the designers’ vision to what the hardware was able to do.

“The UI, in general, had a cool parallax effect as you swiped back and forth, or scrolled up and down through your social feed. That had to be cut, which affected the way text had to be layered over photos and so forth,” Furniss explains.

The 3D effect can be seen at 0:20 mark of the video.

Intelligent Spot and prospects of Kin Three

The eye candy wasn’t the only thing that had to be cut. The video above shows the Spot, one of Kin’s trademark features, featuring a dashboard filled with sections and features. In the final version, all it could do is to serve as a drag-and-drop target for SMS, MMS, and email attachments. Even without any social media integration, it was seen as one of the most clever features of the phones.

The concept video, however, shows the Spot not only sending photos to Facebook or Twitter, but serving as a system scrapbook, storing reminders and sets of objects to share. According to Furniss, it was supposed to be even more than that; “a context-sensitive bucket which you could drop anything into and Kin would figure what you were intending.”

“We were never given a reason for why the Spot wasn’t as powerful as we originally designed it,” Hunter adds. He points to the internal conflict between Microsoft’s managers and multiple mobile teams, reported by Engadget at the time, but did not confirm it from his own perspective.

Kin Two had twice the memory over Kin One, as well as better camera.

Kin has almost instantly built the image of a teenager phone — and that’s the case for oddly-shaped Kin One, marketed to pre-teens and teens. Furniss describes that the Kin Two model, looking like a contemporary QWERTY side slider and having better specifications, was aimed at a 25- to 35-year-olds. (Notably, according to him, Kin One was specifically designed to appeal to the female audience, with Kin Two being a “men’s phone.”)

But looking forward, Microsoft and its partners were already planning to reach another demographic. A third developer, who decided to remain anonymous due to NDAs, shared that Kin lineup was going to evolve as the audience captured by first-generation models changed their taste.

“If Microsoft Kin is a mobile device designed specifically for a younger, millennial audience, our job was to think about how the device needs to change as this audience becomes older,” they describe their role in the project. The source states their team researched the potential new audience and outline new features for the future Kin.

The work made by the developer was left unused, as Microsoft embarrassingly discontinued Kin over its low sales. Later that year, unsold phones got a revised firmware which, stripping social and cloud aspects, allowed to resell them as souped-up dumb phones. The failure of Kin, according to Business Insider, sank the morale within Microsoft.

“Leading up to the launch date of Kin, we were really excited. We were all in creative brainstorm mode for the next big thing, and spirits were high,” recalls Furniss the mood across his team just before the historically poor performance.

“We were given lots of room to explore and encouraged to push the boundaries of what can be done in a traditional mobile UI,” says Hunter from his point of view as Method employee.

The last app-less smartphone

Not only Kin phones had not held their value upon release, but they were also out in the most unlikely of times — both by Microsoft’s mobile divisions and the industry as a whole. Windows Mobile, Microsoft’s legacy mobile OS, was on its last legs, with people having high hopes for all-new Windows Phone. Kin’s mobile platform, having no app support as the world was captivated by them, looked out of place both in the market and in Microsoft’s pipeline.

“When Kin was being designed, it was before this huge paradigm shift to consuming everything via platform-specific apps... I don’t think the social media consumers of today are of the same mindset, they are too used to download specific apps for specific services,” reflects Furniss on how Kin, having no social media clients, embedded their feeds in the UI itself.

On a smaller scale, the idea of unified feed was transferred into Windows Phone, as the People app had a “What’s New” screen showing social media updates. But in 2015, as Facebook had to discontinue one of its APIs due to privacy concerns, Microsoft terminated Facebook integration, with apps like Twitter and LinkedIn dropping it afterward because of the public’s general disinterest. In 2018, commenting on yet another privacy scandals, Facebook called early system integrations “Facebook-like experiences.” The choice of words has clearly separated Facebook as used with apps and browsers and deep system integrations.

Kin phones were the only ones which fully bet on experiences, not apps. From Windows Phone to even more obscure platforms like BlackBerry 10 or Nokia Asha, it was usually a combination of two. The most recent feature phone platform, KaiOS, does not even try integrating social media it the system — but it has an app store and support for web apps.

To win that bet, Kin had to either be as good as planned or cost as much as it deserved. Unfortunately for everyone involved in its creation, it did neither.